Elvis has Entered the Building

In that amazing summer of 1969, I was invited, as Saturday Review's rock critic, to Elvis Presley's debut performance at the International Hotel. I boarded Kirk Kerkorian's private jet with Nat Hentoff and other New York music critics and we flew to Las Vegas, stopping in L.A. to pick up Rodney Bingenheimer and others. I remember deplaning onto the tarmac into the oven of Vegas desert heat and wondering if I had somehow stepped into the jet's exhaust.

We went to the International Hotel, checked into our rooms and then I went out to see the pool. While I was lounging around, a violent wind came up and blew all the deck chairs, tables and shade umbrellas end over end around the pool area. People scattered, shrieking. Most of the deck furniture ended up in the pool.

Enough of the pool for me. I went back to my room and took a nap, which was a huge mistake. I slept and slept. Then, I got a call from an RCA records publicist, very worried why I wasn't "there." Egads. It was show time. Half asleep, I grabbed the clothes nearest me, my best hippie beaded and fringed jeans and a designer cowgirl shirt, never thinking I should have "really" dressed up. I ran downstairs to the showroom entrance where I found out what privilege really means. As I went through the crowd of dressed-to-the nines attendees, I approached the entrance, where a guard frowned at my get-up. He looked purposefully at an impeccably dressed, practically invisible security chief in the corner who gave a quick but definitive expressionless nod and they ceremoniously showed me in, bluejeans and all, carrying no ticket or invitation.

If there had been ten minutes to change, I would have given anything for it, but I wasn't going to miss the beginning of the show. History trumps vanity, according to my set of priorities. And I knew this was an historical event. I was beyond excited. What an opulent room. It was vibrating with expectation.

Thankful for the darkness, I was shown to our ringside table, where I was seated next to Rex Reed, who looked at my outfit and winked. He just loved it. And I just loved him for it. What a sweet man. He was soon to be rewarded for his tolerance, understanding and admiration for quirkiness. He told me he was my fan. I was floored. But there wasn't much time to return his compliment.

The stage lit up. The Dixie Hummingbirds and the Sweet Inspirations began to sing. (Can you imagine them both together?) And with no introduction or fanfare whatsoever, not even a spotlight (!) The King his own self walked out on the stage and began to sing. When he finished, the audience exploded in applause and cheers. When the noise died down, Elvis put the microphone to his mouth, acknowledged his lusty admirers and then turned and took a step toward our table. He looked straight at Rex Reed and pointed. "I saw you on TV the other night," said Elvis Presley to Rex Reed and the world. Rex Reed leaned back in his seat, put his hands to his face and said, "Oh, my God, I think I'm going to die."

Elvis' performance was legendarily and extravagantly wonderful. It has been copiously described elsewhere, so I won't go into it here. I realized that if I lived long enough, all my wishes would come true. What I, or any young girl, would not have given in the nineteen fifties to see Elvis in person from the first row. At the time it wasn't as big a deal to me as a Who or a Rolling Stones concert, but in retrospect, the uniqueness of the event sits side by side with other peak experiences.

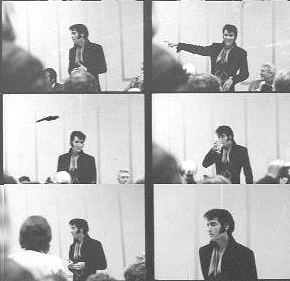

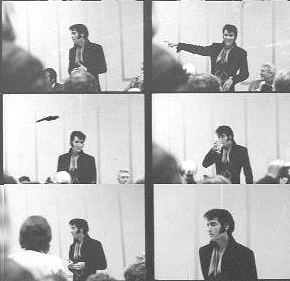

After the performance, we (the press and other invited guests) were herded into a nondescript room near the showroom, where Elvis gave an unannounced, but nonetheless triumphant, press conference. These are some of my never before published pictures from the 2x contact sheet of that delightful confab with an ebullient Elvis Presley.  "Do you have to be as reclusive as you used to be?" I asked. He chortled and said "I'm not that reclusive, really, I'm just sneaky." One snotty woman asked "Do you dye your hair?" and Elvis answered "Oh, c'mon." I was lucky to get these pictures.

"Do you have to be as reclusive as you used to be?" I asked. He chortled and said "I'm not that reclusive, really, I'm just sneaky." One snotty woman asked "Do you dye your hair?" and Elvis answered "Oh, c'mon." I was lucky to get these pictures.

As if seeing Elvis were not enough, Ike and Tina Turner were playing the smaller lounge. What a show that was! Between you and I, I enjoyed it more than Elvis's show. I ended up reviewing the Turner's (Fussin' Fightin' and Carryin' On) album instead of the Elvis show in the next issue of Saturday Review. It wasn't that I was ungrateful (as extravagant a junket as that was, I never did reviews out of gratitude anyway). Rather, I felt the Turners were more a part of what was culturally important at the time. The rock audience would come to know Tina Turner as an unrelenting pop dynamo with more energy than any other ten acts put together, as well as the poster child for an abused wife and a woman who overcame adversity, to say nothing of an ageless wonder of timeless beauty and appeal. Eventually she would leave Ike behind, tour with The Rolling Stones, have her autobiography made into a major motion picture and headline her own major road shows. If you ask me, though, the show was better when Ike was running it.

Elvis Presley's re-emergence was news, it was exceptionally important and --arguably-- supreme entertainment.

Some purists, in hindsight, thought it lacked the guts and gristle of the "real" Elvis and complained that the set relegated the older hits to medleys. Regardless of any of that, though, it just didn't fit in with the politics of my column as I saw it. Maybe if I had been a country music fan, I would have conceded that it was a culturally important event, but I wasn't. That was a my call and I stand by it. Elvis was a landscape-changing shockwave in the time of his initial emergence, but this redux, at least to me, did not contribute to nor did it materially affect the course and effect of the rock movement and the politics of the sixties. It could be argued that Presley himself wanted no part of it and more power to him---that was his call to make. In his sphere of influence, he ruled the roost. The once and future King.

Ellen Sander

"Do you have to be as reclusive as you used to be?" I asked. He chortled and said "I'm not that reclusive, really, I'm just sneaky." One snotty woman asked "Do you dye your hair?" and Elvis answered "Oh, c'mon." I was lucky to get these pictures.

"Do you have to be as reclusive as you used to be?" I asked. He chortled and said "I'm not that reclusive, really, I'm just sneaky." One snotty woman asked "Do you dye your hair?" and Elvis answered "Oh, c'mon." I was lucky to get these pictures.